Strategy, Legal & Operations

Not all carbon offsets are equal— a guide to help you pick the right schemes

Duncan Oswald CEnv FIEMA, Climate Science Lead at Sage Earth, takes a look at the complex world of carbon offsetting, giving you a guide on what to look out for.

At Sage Earth, we have committed to a target of net zero emissions by 2025. In the meantime, we offset all the emissions we cannot eliminate, so that we can deliver on our commitment to be carbon neutral.

To ensure that our claims are credible, we use the specification PAS 2060:2014. “Specification for the demonstration of carbon neutrality.” Looking specifically at section 9.1.2, which sets out the requirements for offsetting residual GHG emissions in PAS compliance, the main relevant criteria are that offset carbon credits should be able to demonstrate additionality and permanence, and that they should avoid leakage and double-counting. The PAS also requires that carbon credits must relate to emissions reductions (or avoidance) which have actually happened: you can’t balance past emissions with future offsets.

What do these terms mean?

Additionality means that offsetting activity wouldn’t have happened without the incentive provided by selling carbon credits. Examples of where this is not the case include schemes where credits have been sold to protect forests from logging, where logging would have been illegal anyway because the forest was in a National Park.

Permanence is referred to in the GHG Protocol with reference to “reversibility.” The Protocol requires that “the risk of reversibility should be assessed, together with any mitigation or compensation measures included in the project design.” Examples of offsets that have demonstrated reversibility (and therefore, did not have permanence) include vast areas of plantations and protected forests on the US west coast which have been destroyed in recent wildfires caused by climate breakdown.

Leakage refers to a carbon offset project which may inadvertently result in greater emissions elsewhere. Examples include forest protection initiatives which lead to increased logging outside the protected area, or energy efficiency improvements which lead to an increase in production, and no reduction in emissions.

Double-counting is when 2 separate entities are sold the same carbon credit. Buying carbon credits that are verified by an independent third-party verifier should prevent this.

Actuality requires that carbon credits are generated by activities that have actually happened, rather than those that (probably) will happen in the future. If you have emitted a tonne of carbon dioxide over the last year, offsetting it over the next decade doesn’t work, so it isn’t allowed. This can occur in the case of tree planting projects as the activity which offsets the emissions (growing) happens after the offsets have been sold.

The PAS sets out the requirements for buying carbon credits to achieve carbon-neutral status, but they are not widely understood. This means that many offsets bought to balance emissions are not effective.

Here are a few examples of commonly used offsetting schemes and reasons why they often don’t comply with the PAS:

Additionality:

- Many emissions avoidance (rather than carbon drawdown) schemes, e.g:

- Renewable energy: it’s the cheapest form of energy, so why would you not build it anyway?

- Avoided deforestation: can you be certain it would have been felled if you had not intervened?

Permanence:

- Tree planting: how sure are you that the trees will grow, and that they won’t die or be burned down?

- Peatland restoration: with changing climate, how permanent is your restoration?

Leakage:

- Schemes where activity can be displaced or increased, e.g.:

- Avoided deforestation: you might stop logging here, but are you just displacing it somewhere else?

- Energy efficiency: where the benefits can be wiped out by increased production.

Double counting:

- Any project not verified by a reputable independent third party.

- Linked to permanence: have you been reimbursed for protected forests that burned down? Have you re-invested?

Actuality:

- Has the scheme you’re paying for already achieved the carbon credits it’s selling?

- Tree planting

- Peatland restoration

- Avoided deforestation

- Advanced weathering

- Renewables: are offsets based on what fossil generation was actually displaced, or an exaggerated estimate of total emissions displaced by the project over its lifetime (e.g. IFI methodology)?

Problem areas for these types of projects

Have a look at any offset provider (for instance, Persefoni), and see how many of their schemes fit these criteria: how many have already happened, would not have happened without your money, will last forever, will eliminate (not displace) climate impacts, and are investment-grade reliable? Look at the carbon-credit rating systems (Gold Standard and Verra, for instance) in the same light: the information they publish is often enough to reject schemes against the PAS criteria, even if it is often insufficient to approve them.

This is not to say that the projects these carbon credits fund are not worthwhile. Many of them absolutely are. They can have all manner of benefits, such as protecting and enhancing biodiversity, raising awareness, and even reducing future emissions. But what very few of them do is offset the emissions caused by your business so that you can claim that you are carbon neutral. To do this means you have calculated your emissions, and paid to offset them with robust carbon credits which fulfil all the PAS 2060 criteria.

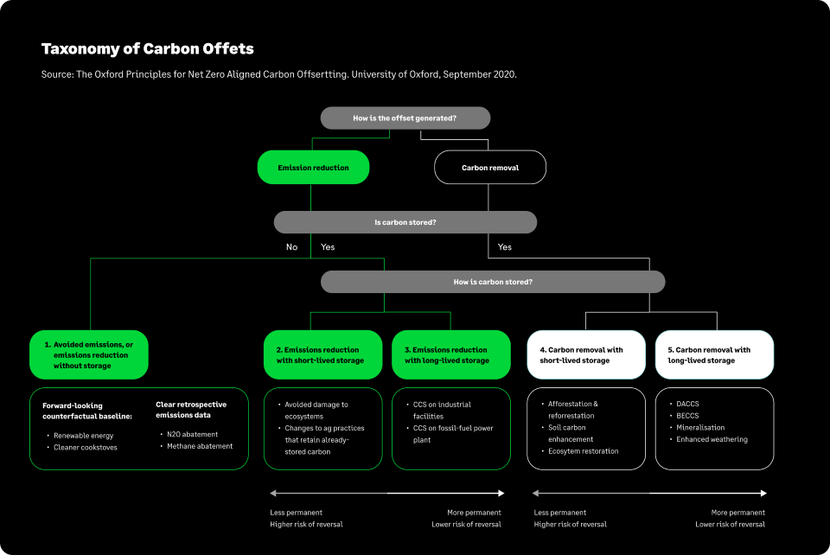

An important point on which the PAS is silent, is whether carbon credits should be supported by drawing down GHGs already in the atmosphere, rather than avoiding or reducing emissions. As the Taxonomy of Carbon Offsets from the Oxford Principles describes in the chart below, there is a hierarchy of offset quality. Eventually, all offsetting will have to shift to carbon removal (as there are no longer any emissions to reduce, and as reducing atmospheric GHG concentrations becomes ever more critical), but for now, and within the constraints of the PAS described above, carbon neutrality can be officially achieved both by reductions and removals.

It should be noted, however, that many of the examples along the bottom of the figure above would not be PAS 2060 compliant:

- On any meaningful scale, BECCS has insurmountable leakage problems.

- Mineralisation and enhanced weathering are slow-acting, so hit problems with the requirement that credits be historical.

- CCS would work in principle, it just hasn’t yet in practice.

- It is hard to prove the additionality of avoidance and protection schemes.

- Abatement of emissions can work, provided the additionality is robust.

- While renewable energy is unarguably a good thing, it is hard to prove what emissions it displaced, particularly retrospectively.

As you can see, it can take a bit of research to establish whether credits are effective in this regard, and it doesn’t help that the offset providers and ratings agencies don’t align their criteria with the PAS. We plan to integrate our carbon-credit research into the Sage Earth platform soon, but for now we are focussing on the accuracy of our automated carbon accounting, and linking the resulting footprints to robust and effective mitigation measures.

So, within the constraints of the PAS, what sort of projects can be used to offset emissions towards carbon neutral status? To a large extent, it depends on the specific details of the project, and to a lesser extent, on what is available and how much you are prepared to compromise, but some that definitely fit the bill include:

- Direct Air Carbon Capture and Storage

- Bio-oil reinjection

- Biochar (maybe; permanence is uncertain)

- Emissions abatement (e.g. methane, NOx, F-gases; provided additionality is robust)

Although it’s nothing to do with any official carbon-neutral declaration, another good tip is to hedge your bets. Once you’ve calculated your emissions, offset them twice over to hedge against uncertainty in carbon credits. Spread the risk by supporting a range of projects; and remember, the climate crisis is only part of the picture: once you’ve addressed your climate impact, there’s no harm in doing some good in other areas.

Our chosen scheme:

Having reviewed a number of schemes on the market Sage Earth selected Tradewater carbon credits to offset our 2021 to 2022 carbon footprint. These credits are generated from 2 main activities:

F-gas disposal

Tradewater locates, purchases and destroys stocks of refrigerant gases, principally from regions where they would not otherwise be disposed of properly. These gases have a global warming potential many thousands of times higher than carbon dioxide, so avoiding their accidental release into the atmosphere is an effective way to reduce global climate impact.

Methane abatement

These projects rely on the capture and burning of methane which would otherwise leak from abandoned coal mines. Every tonne of methane that escapes has the same impact as at least 28 tonnes of carbon dioxide, and each tonne of methane burned results in 2.75 tonnes of carbon dioxide, so these projects reduce climate impact by at least 90%.

We have also made the decision to offset the period of 9 months before our 1st financial year using a pro-rata approach.

Did you know that Sage has a new Carbon Accounting software solution?

If you use either Sage Business Cloud Accounting or Sage 50, Sage Earth can help you better understand your business's environmental impact and guide you to net zero emissions.

Ask the author a question or share your advice